Introduction

In the previous post I took a look at a data modelling exercise in C#, I designed a data model to represent a card in the standard 52-card deck.

We saw some of the problems we face when designing data models in an object oriented language, particularly the lack of ability to express that a certain object can have a value of multiple different types, but it can have a value of only one of those types at any one time (a card is either a value card, a face card, or a joker).

We can get around these limitations by implementing custom validation logic that forces us to create only valid instances of a given class, but it can leave us wondering why cannot the type system help us express our intention more clearly.

In this post we’ll see how we can desing the same data model in F#, and how some constructs of functional programming can mitigate some of these limitations.

The task

We will solve the same assignment: design a data model to represent a card in the standard 52-card deck.

You can find a detailed description of the exercise in the previous post.

Data types in F#

Since I expect most readers to be less experienced in F# than C#, I’ll give a brief introduction to the basic data types of F#, to have a baseline for any further discussion.

Record types

Records are the basic data types we can use to model a complex entity with multiple fields. We can think about them as immutable structs, which only have public fields, and don’t have behavior. (Technically we can define member methods on records, but it’s not an idiomatic thing to do in F#.)

type Customer = {

Id : int

Name : string

Email : string

}

We can create an instance of a record with the following syntax.

let cust = {

Id = 5,

Name = "Jane Smith"

Email = "[email protected]"

}

Two interesting things to note:

- We don’t have to specify the type. If it is unambiguous, the compiler will infer the proper type for our value.

- It is mandatory to specify every field of the record. If we skip one, we receive a build error. This is a great thing to ensure that we update every place depending on our type when we add a new field, and to keep a strong coherence among the fields of any record type.

More info in the docs.

Tuple

Similarly to other functional programming languages, F# provides convenient syntax and support for using tuples. We can create a tuple of multiple values simply by listing them between parens, separating them with commas.

let point = (1.5, 4.3)

let personWithAge = ("Jane Smith", 25)

F# also supports pattern matching with tuples (which is again a typical feature of FP languages, and to some extent it also arrived in JavaScript in the form of destructuring):

let x, y = point

We can also specify tuples in type declarations, where if we want to define a tuple of 3 elements, we can use the following syntax.

type MyTuple = string * int * Customer

Discriminated union

This is another basic F# data type which will be particularly interesting in our exercise. Its name is a bit scary at first, but the concept is very simple.

At first sight a discriminated union looks like an enum in C#, for example we can define a logging level with it.

type LoggingLevel =

| Debug

| Info

| Error

However, a discriminated union is more than this. Every case we define (which is called a named case) can also have a value associated to it, and the different cases can have different values.

An idiomatic example from the official documentation.

type Shape =

| Rectangle of width : float * length : float

| Circle of radius : float

(Note that we can also see here the syntax for specifying a tuple type.)

Then we can construct a value of the different cases by specifying the case name.

let rect = Rectangle (length = 2.3, width = 10.0)

let circ = Circle (2.0)

And when we actually want to use a value with a discriminated union type, we can use pattern matching to handle the different cases.

let calculateArea shape =

match shape with

| Rectangle (w, l) -> w * l

| Circle r -> r * r * 3.14

We can think of discriminated unions as a way to achieve static, compile-time polymorphism. (Static, because all the cases of the union are defined in one place, and there is no way to extend the union with other cases from the outside, as opposed to OO inheritance. We could try to model this behavior in OO by defining an abstract base class, and creating some sealed derived types. But even this could not prevent the users of our library to introduce additional derived types in the same hierarchy.)

One of the nice benefits of having all the cases of the union defined in one place is that the compiler can check if we always cover all the cases everywhere we are doing pattern matching on a certain union type, which is extremely handy when we introduce a new case, so the compiler can remind us to update all the places in our codebase which are using the union.

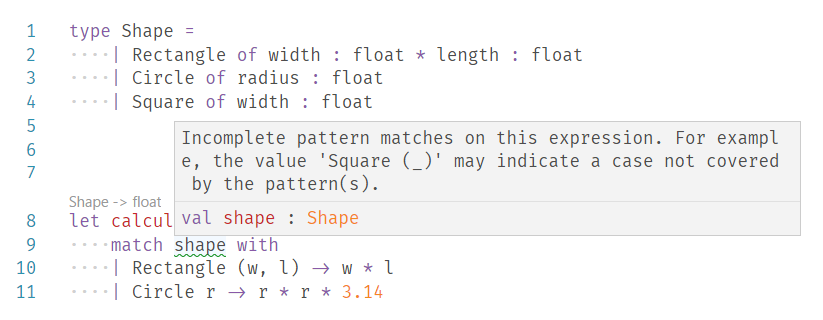

For example if we introduce a new Square case for our Shape union, we’ll get this nice warning message.

Implementation

In order to implement the card data model in F#, we can start the same way we did in C#, by defining the types representing the various suits and faces. In C# we used an enum for this purpose, in F# we can use discriminated unions.

type Suit =

| Hearts

| Spades

| Clubs

| Diamonds

type Face =

| Jack

| Queen

| King

| Ace

The next step is to create the actual data type which will represent a card from the deck. Remember: what we want to express is that the card is either one of these options.

- A value card with a suit and a number value.

- A face card with a suit and a face.

- A joker.

This is exactly the kind of concept we can clearly express using a discriminated union.

type Card =

| FaceCard of Suit * Face

| ValueCard of Suit * int

| Joker

We can create some actual values of this type with the following sytax.

let jackOfHearts = FaceCard (Hearts, Jack)

let threeOfClubs = ValueCard (Clubs, 3)

let joker = Joker

Some things to notice:

- There is no way to create a value which is “both” a face and a value card (or a joker). Every value falls exactly into one of the cases.

- The definition of the discriminated union forces us to provide the necessary input when we create a value, namely, the suit and face in case of a face card, the suit and the value in case of a value card, and nothing in case of a joker. (And there is no way to provide or set “more” data then what the specific case of the union needs.)

So with the 4 lines of code defining the Card union we achieved the same goal as what we did in C# with the following implementation.

class Card

{

public Suit Suit { get; }

public Face? Face { get; }

public int? Value { get; }

public bool IsJoker { get; }

private Card(Suit suit, Face? face, int? value, bool isJoker)

{

Suit = suit;

Face = face;

Value = value;

IsJoker = isJoker;

}

public static Card CreateFace(Suit suit, Face face)

{

return new Card(suit, face, null, false);

}

public static Card CreateValue(Suit suit, int value)

{

return new Card(suit, null, value, false);

}

public static Card CreateJoker()

{

return new Card(default(Suit), null, null, true);

}

}

This illustrates how powerful and concise construct a disciminated union can be, and since I got familiar with it, I miss it every day when doing OO development in C#.

Finally let’s take a look at what it looks like if we want to actually process a value of this type, for example if we want to implement the score calculation of the card game Rummy. Here we can see the pattern matching syntax again.

let calculateValue card =

match card with

| Joker -> 0

| FaceCard (Spades, Queen) -> 40

| FaceCard (_, Ace) -> 15

| FaceCard (_, _) -> 10

| ValueCard (_, 10) -> 10

| _ -> 5

And this is how we can call this function with a value we created.

let jackOfHearts = FaceCard (Hearts, Jack)

// The value of rummyScore will be 10.

let rummyScore = calculateValue jackOfHearts

With this exercise I wanted to illustrate how the type system and the language features of F# can help us express some constructs which are inconvenient to model in object oriented languages. Particularly the discriminated union is a data type that I really recommend for every developer to get familiar with (of which the only downside is that we’ll be constantly wishing we had this feature in every language :)).

At first sight this example might seem a bit specific, but these scenarios pop up in every day work much more than we’d expect. Let’s look at a couple example.

The result of an operation that might not found the result, or return an error.

type OperationResult =

| Success of data : Data

| NotFound

| Error of errorMessage : string

An HTTP request, which is either a GET (having only a URL) or a POST (having a URL and a body).

type HttpRequest =

| Get of url : string

| Post of url : string * body : byte array

A data type representing credentials, either with username and password, or a certificate.

type Credentials =

| UserPass of user : string * password : string

| Certificate of certFilePath : string

| None

Learning about these functional programming features greatly changed how I think about data models and interface design in my everyday work (programmign in OO languages).

With this post I wanted to give a brief introduction to these constructs. I hope these examples will provide motivation to get familiar with F# and functional programming.