Throughout most of my career I worked with Microsoft technologies, mainly with .NET and C#. This meant that my daily driver operating system has mostly been Windows, as even after the advent of .NET Core (which can be run on Linux), I had to maintain some classic .NET applications, which only ran on Windows, and could only be easily developed with Visual Studio.

But I had a short period of time during which I mainly worked on some TypeScript and NodeJS applications, and did not need Windows for my day to day work. Thus I decided to try to use Linux on my development machine. Due to my lack of experience, setting everything up and took some effort, and I remember having some struggles with certain device drivers.

One thing that made all of that worth it was to be able to use a tiling window manager. If you—like me—are mostly a Windows user, might ask what a tiling window manager is in the first place. Let’s start at the beginning.

The Windowing System

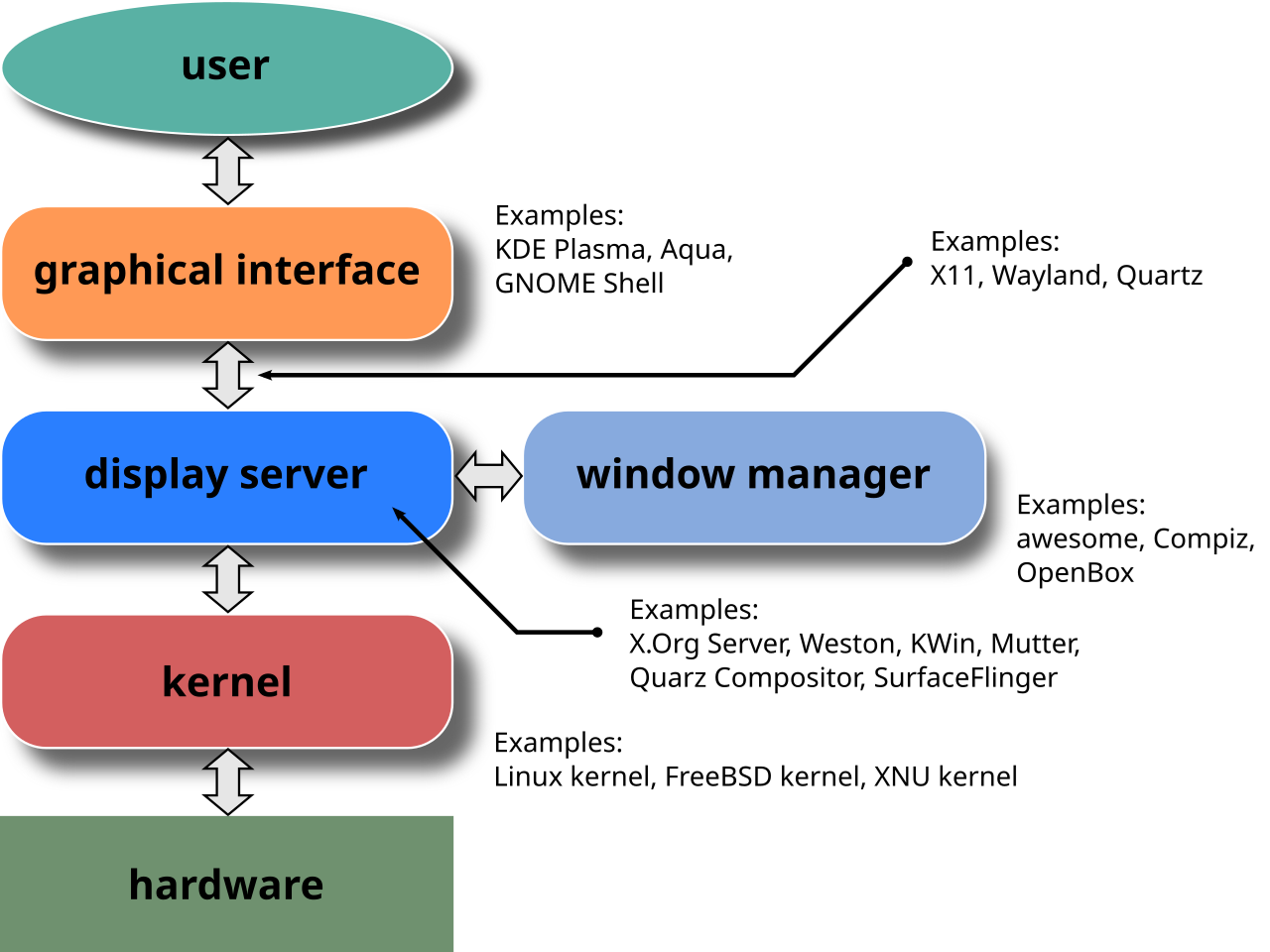

The windowing system is the part of the operating system responsible for drawing windows with their various UI components like icons, buttons, borders, etc.

A central part of the windowing system is what’s called the “display server” or “window server”, which provides an API for the various programs to render themselves on the screen, and it connects to the OS kernel to receive input from the different attached input devices, such as the keyboard and the mouse.

And another thing is the “display server communication protocol”, which is the API contract provided by the display server to the various applications.

(The terminology around this is not perfectly clear. Even the Wikipedia page at some point says that the display server is “the main component of the windowing system”, but later it says “The display server implements the windowing system”. And based on my experience the distinction between the communication protocol and the windowing system as a whole is not strictly defined. So I think these terms are used somewhat interchangeably.)

Examples

To find concrete examples for windowing systems, we mainly have to look at Linux.

On Windows, there is a dedicated windowing system since Windows Vista called Desktop Window Manager, but to be honest I haven’t heard anyone using this name before reading up on it for this post. And I could not find out if there was a specific windowing system in Windows before Vista, or this functionality was just considered an integral part of Windows.

On the other hand, on Linux the display server is another modular component of the system that we can choose an install, so the distinction between it and the rest of the OS is much more often defined and discussed.

Arguably the two most well-known windowing systems for Linux are X and Wayland. The X Window System (or simply X) is a long existing project, initially released in 1984, which served as the most common choice to implement GUI applications on Linux for a long time. It is also referred to as X11, because the X protocol has been at version 11 since 1987. If you have used any GUI application on a Linux desktop machine not very recently, it was almost certainly using X.

A more recently introduced Linux windowing system is called Wayland, which is intended to be a successor of X, and it is now the default for multiple popular Linux distributions, like Ubuntu, Fedora and Debian.

There are other display server implementations out there, but their usage is less common, or they are mostly targeting scenarios other than desktop PCs, for example Mir, which is mostly used for Internet of Things applications.

Desktop Environment

In order to be able to use our desktop computer for everyday tasks involving GUI applications, we need a system running on top of the OS utilizing the display server to provide us a way to start applications and switch between them, and potentially provide other convenience features, like displaying a list of the running apps, providing a status bar, being able to resize application windows, etc.

One such type of software, arguably the one which is most widely used, especially by non-technical users, is a desktop environment. A desktop environment is a software and potentially a bundle of additional loosely connected programs, implementing features we are used to see on the GUI of a desktop PC, such as icons, windows, toolbars, wallpapers, and various additional desktop widgets, and it often also supports drag and drop interaction. As Wikipedia states:

A desktop environment aims to be an intuitive way for the user to interact with the computer using concepts which are similar to those used when interacting with the physical world, such as buttons and windows.

Popular Linux desktop environments include GNOME, KDE and Xfce, each being the default for some distributions, like GNOME for Ubuntu, KDE for openSUSE, and Xfce for Manjaro.

And on Windows the desktop environment is called the Windows shell, although I haven’t heard this name being explicitly used much before, since on Windows the GUI is typically considered an intrinsic part of the OS and not a standalone component.

Window Manager

Desktop environments provide a fully fledged GUI suitable to be used by everyday non-technical users. A Window manager is a software controlling the placement of windows on the screen. A desktop environment typically includes a default window manager, for example GNOME uses Mutter, and KDE uses KWin by default.

However, a window manager can also be used by itself in lieu of a desktop environment to be the main way to interact with the system. This approach is typically chosen by power users, as setting up a window manager is less streamlined, their feature set is more low level and lightweight, and controlling them often includes several hotkeys which need to be memorized.

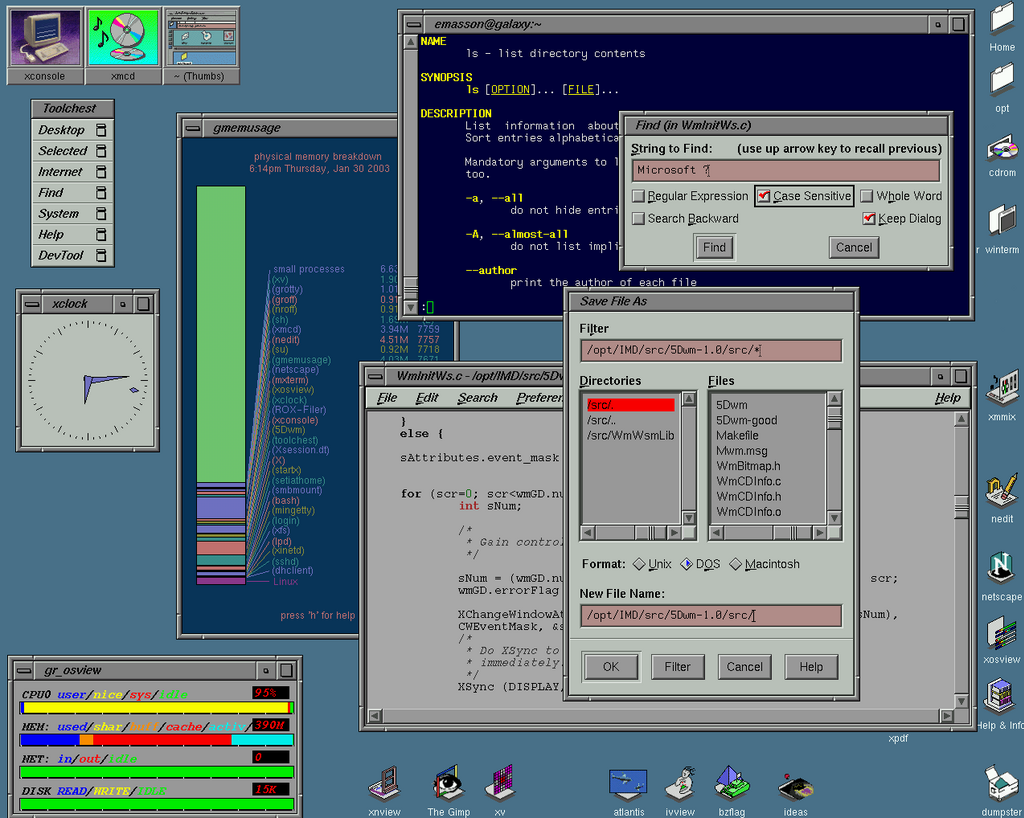

Window managers are typically categorized based on how they support positioning windows on the screen. For example stacking window managers typically support freely moving and resizing windows, which can cover each other.

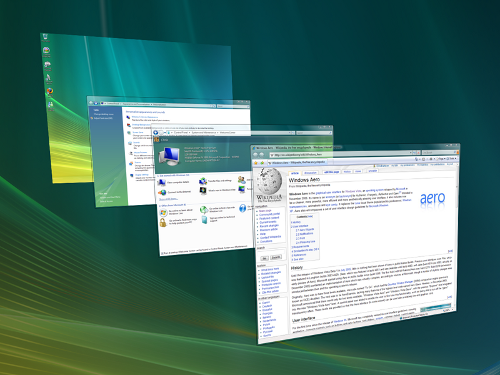

Compositing window managers (or compositors) typically implement fancy effects such as 3D transformation, blending, fading, drop shadows, etc. A prominent example for this is the Desktop Window Manager in Windows introduced in Vista, which added 3D effects, or Compiz for Linux, which is known for its 3D transformations, for example rendering windows on the surface of a cube.

Tiling window managers

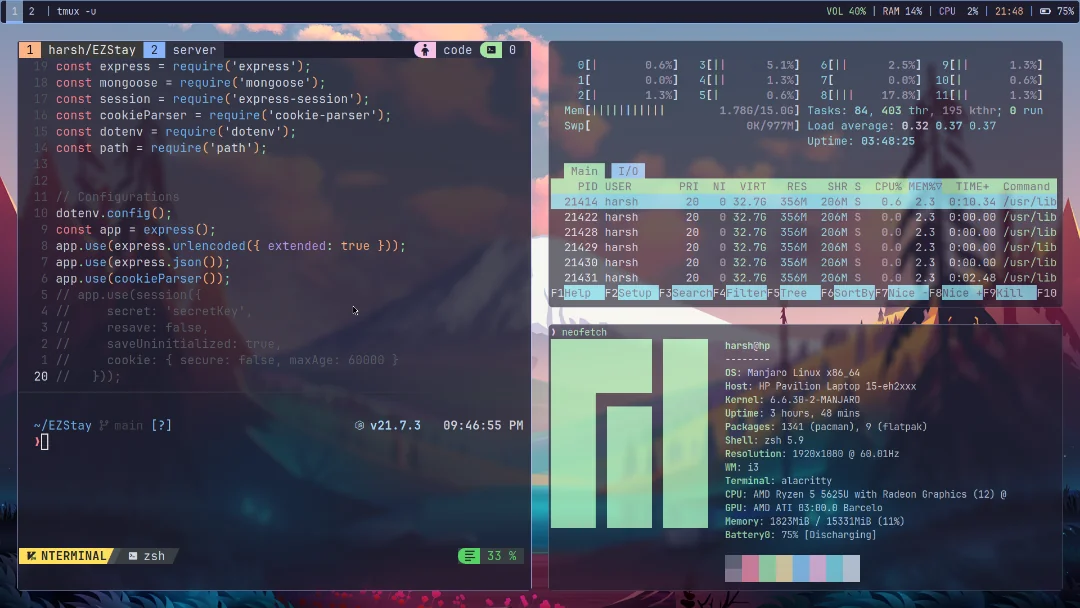

The type of window manager most often used by power users and developers is the tiling window manager. Instead of opening windows stacked on top of each other, and allowing for the windows to be freely movable and resizable with a mouse, a tiling window manager automatically positions and sizes windows so that they are evenly distributed on the available screen real estate. When your screen is empty, and you open a new window, that opens full screen. If you open a second window, then typically the screen will be split in half for the two windows, and so on—hence the name tiling.

Usually windows can be moved or resized with keyboard shortcuts, and their distribution can be switched between horizontal or vertical.

This setup can be very efficient for folks used to mainly using the keyboard and memorizing shortcuts, especially for development when working with terminals, where we often want to open multiple shells and/or code editors open at the same time, which fits the tiling layout really well. There are several such window managers, some still actively maintained ones for X are i3, awesomewm and dwm. As the basics of the tiling system can be implemented with relatively little amount of code, several other projects exist created in all sorts of programming languages. My favorite example is xmonad, which is a tiling window manager implemented in Haskell, as indicated by one of the photos on its website 🙂.

As Wayland is a modern alternative to X, new and more modern window managers appeared targeting it. One example is Sway, which is a drop-in replacement for i3. And the one which seems to have the most buzz is Hyprland. While some other window managers like ratpoison intentionally don’t want to support any fancy effects such as animations, custom border designs, etc. Hyprland has extensive support for eye candy to be able to create a really aesthetically pleasing yet functional UI.

I have always liked tinkering with things like shell prompt themes, coding fonts and color themes, so I find the customization capabilities of Hyprland really impressive, and it’s something that makes me consider switching to Linux once I don’t need Windows for my day to day work.

Ricing

There is a whole subculture of customizing the UI of desktop environments or window managers, including terminals, shell prompts, IDE color schemes, etc., as illustrated by such subreddits like desktops, unixporn and terminal_porn.

(For whatever reason, this is called “ricing”. I’m not sure about the exact etymology of this term, but apparently this phrase has already been used by race car enthusiast, referring to the process of customizing a car in a flashy way to make it look more sporty.)

This can involve several things: selecting a window manager, a shell and a terminal emulator, various panels, bars and widgets. And it can also get really elaborate and involve sophisticated custom development, as illustrated by this video by zacoons, who won the last “rice contest” organized by Hyprland.

If you want to spruce up your desktop, a useful resource is the awesome-ricing repository, which has an exhaustive list of various resources, including window managers, terminal emulators, shells, and all sorts of widgets and UI components.

Tiling on Windows with GlazeWM

Back when I temporarily switched from Windows to Linux more than 5 years ago, and really enjoyed using i3, I investigated a bit whether there is a mature tiling window manager available for Windows which would provide a similar experience, and at the time I could not find any.

But luckily things have changed since then, and now there are definitely viable options out there, see a list here.

The two most popular options seem to be GlazeWM and Komorebi, both implemented in Rust (Rust is definitely having a moment, huh?).

I started using GlazeWM both on my desktop PC and my laptop a couple of months ago, and didn’t look back. Once a handful of the basic keywords are learnt, and some of the config is customized to our liking, it can make interacting with the UI really joyful and efficient.

By default GlazeWM opens every window tiled, evenly distributed over the screen real estate, either vertically or horizontally. The windows can be moved around, temporarily minimized or switched to full screen mode. Multiple workspaces can be created and switched between, and moved across monitors, all while using only keyboard shortcuts.

By the way, providing built-in support for animations is also in the works, which will make the experience even more fluid and aesthetically pleasing.

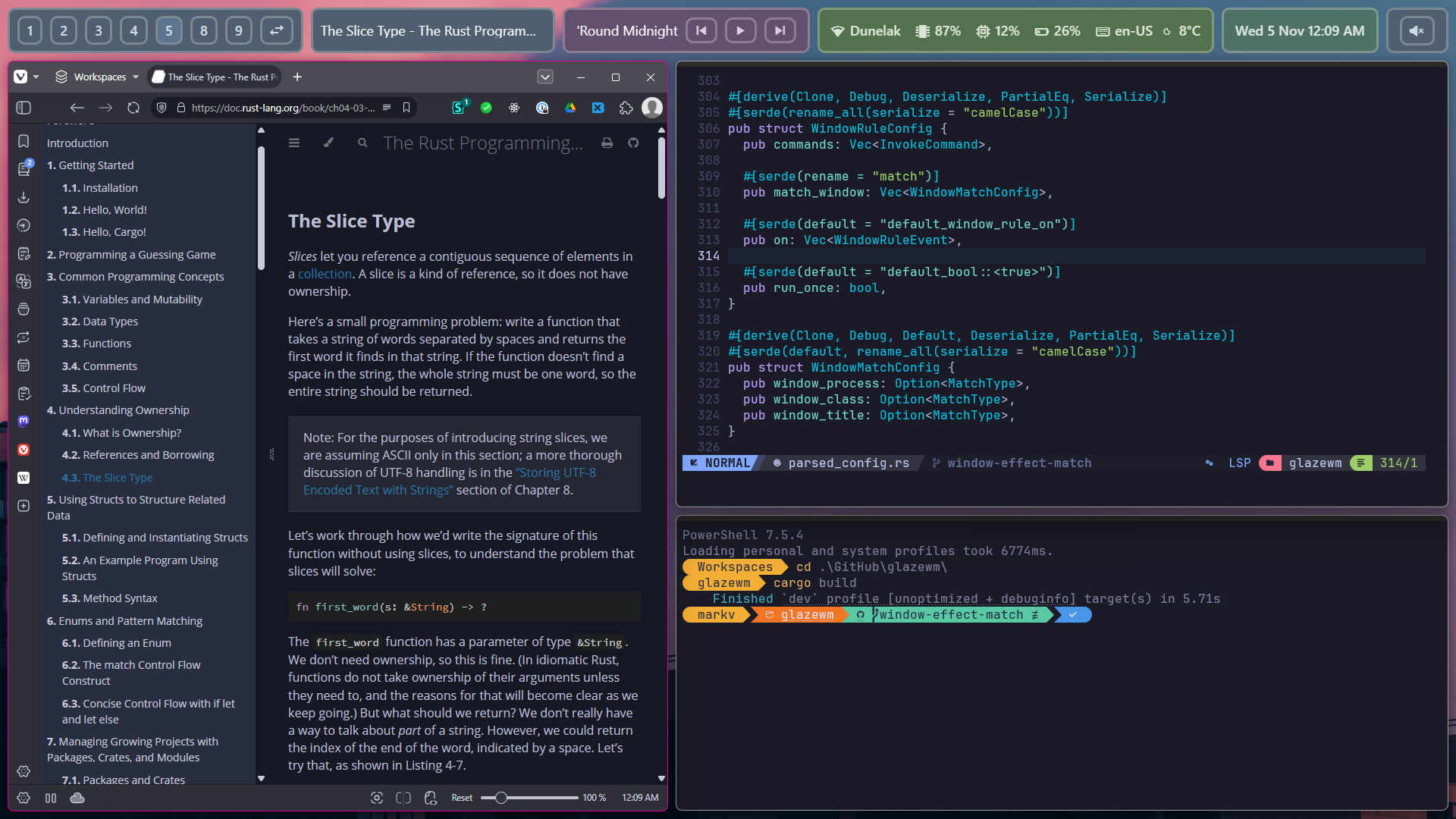

Top bar

When using a tiling window manager, it is common practice to display a “bar” at the bottom or the top of the screen, showing the workspaces, the time and date, and various other status information of the system. On Windows we could also use the built-in taskbar for this, but there are some other, more customizable alternatives as well. By default, GlazeWM uses Zebar, which is an open source status bar implemented in—you wouldn’t guess it—Rust 🙂. It’s highly customizable, its UI can be completely replaced with HTML and JavaScript. The screenshot above shows a custom layout I implemented with React.

Another popular option seems to be YASB implemented in Python, which also looks really cool, but I haven’t tried it yet, since I’ve been quite happy with Zebar.

Application launcher

For Linux, several “application launcher” tools exist, with which programs can be quickly started, such as dmenu and rofi.

On Windows, the built in Start menu could serve this purpose, we can start an application by pressing the Win key on the keyboard, typing in the name of the app, and pressing Return.

But I don’t think this is ideal, for two reasons: when using a window manager like GlazeWM or Komorebi, we typically want to hide the built-in Windows taskbar, and rather use another bar like Zebar. But when we press the Win key, that opens not just the Start menu, but it also temporarily shows the otherwise hidden Windows taskbar, which looks a bit clunky.

And also, I’ve sometimes had a bad experience with the Windows Start menu, it tends to be randomly quite slow at times, show suggestions I’m not interested in like Bing search results, and for me it occasionally even completely stopped working, which could only be fixed by restarting the explorer.exe process.

Thus I tried looking for an alternative available for Windows. One tool I found that I’ve been using and am happy with is Command Palette, which is part of the PowerToys suite of power user utilities. Command Palette can be used to quickly start applications and execute systems commands. It can be configured to be started with a preferred hotkey, I configured it to use + R, thus it replaces the built-in system Run dialog (about which I’m not yet 100% sure if it’s the best idea, but I have not been missing it much since then).

Tips and caveats

Learn the keyboard shortcuts piecemeal. You only need a handful of shortcuts to start being productive with GlazeWM. I find the ones used for switching between and moving windows and workspaces the most essential. A useful cheatsheet can be found in the GlazeWM GitHub which gives an overview to help learning.

Tinker with the configuration, including changing the keyboard shortcuts. The config file can be found at ~/.glzr/glazewm/config.yaml, and a lot of config parameters can be customized to our liking, including all the hotkeys. Depending on your workflow, some default shortcuts might be clashing with other functionalities. The main ones for me were Alt+D, which I use to focus on the browser address bar, and the Alt+arrow keys which normally navigate in the history of the browser or Explorer windows.

Some visual aspects, for example gaps between windows (which we can set to 0 if we want to fully utilize all the screen real estate), or the highlight border color can be adjusted, which I’ve set to a more vibrant color to make it easier to identifier the active window.

To be able to open the configuration easily from anywhere, I added this alias to my PowerShell profile:

function OpenGlazeConfig {

nvim C:\Users\markv\.glzr\glazewm\config.yaml

}

New-Alias glazec OpenGlazeConfig

With this in place, I can open the config by simply typing glazec.

Some apps don’t play nicely with GlazeWM. If you encounter issues with a specific application, you can add a window rule to the configuration to make GlazeWM ignore it, as shown in the documentation. To find the title, process and class attributes of certain window, various tools like WinSpy can be used.

For example the Command Palette shown before should be ignored, as we would like it to open as a floating modal instead of being tiled.

And another big one for me was Paint.NET, which for some reason had a dialog window which kept resizing itself in an infinite loop and eventually crashing, so I had to configure it to be ignored to make it operational.

window_rules:

- commands: ['ignore']

match:

...

- window_title: { equals: 'Command Palette' }

window_class: { equals: 'WinUIDesktopWin32WindowClass' }

- window_process: { includes: 'paintdotnet' }

Be conscious regarding how to split windows. Once we start using a tiling window manager, we’ll get one more way to quickly split the available screen space in two. This can further complicate our workflow if we are already used to splitting either terminal or editor windows.

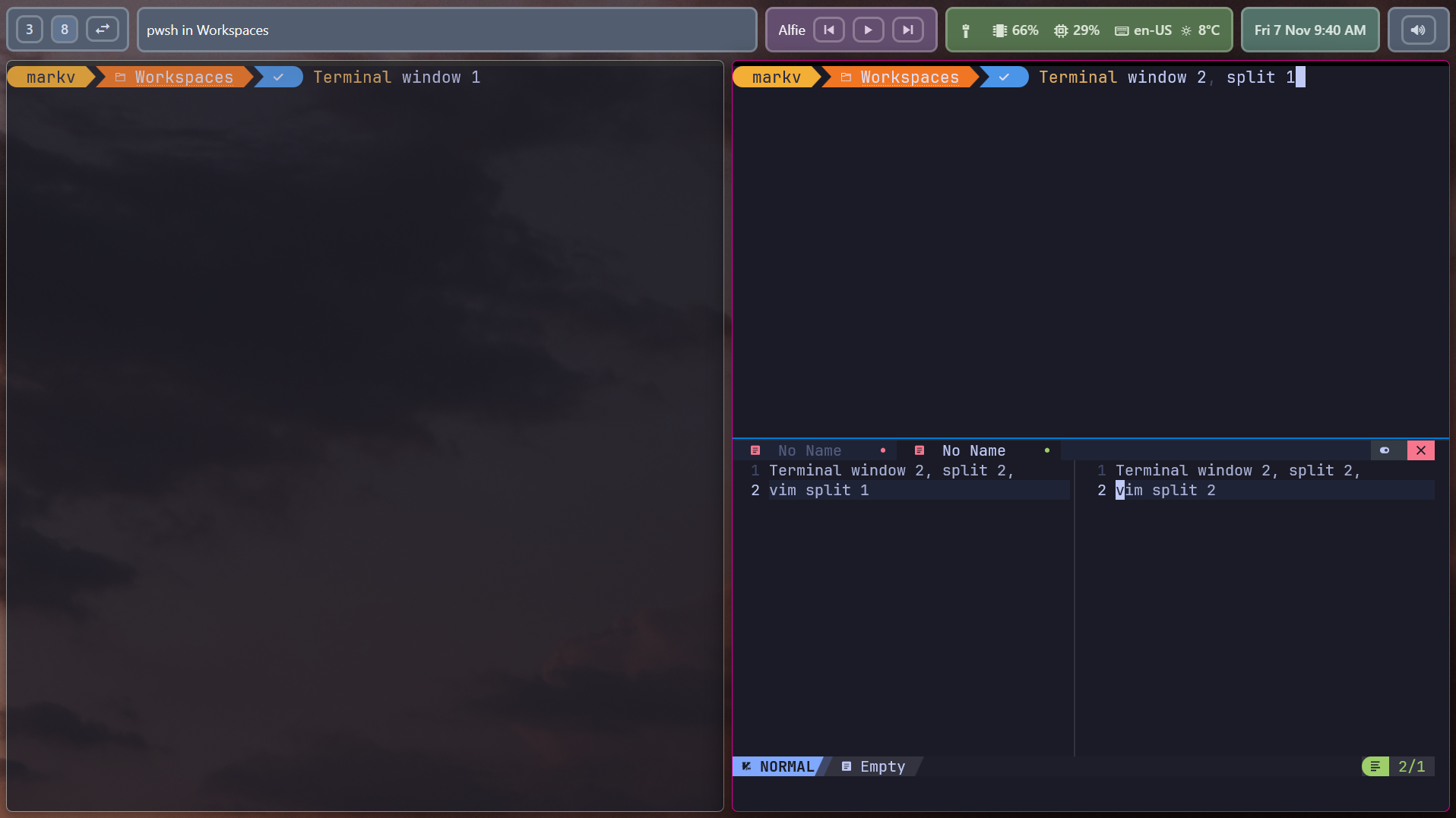

Here is a screenshot illustrating this.

In this screenshot we split the screen in three different ways:

- First we have two separate terminal windows open, splitting the whole screen vertically.

- The right terminal is split in two horizontally, using the split functionality of Windows Terminal.

- The bottom split has vim open, which has two separate tabs, splitting the editor vertically.

This setup can get quite confusing, it is easy to get lost and fail to keep track of where we are, and configuring and memorizing the hotkeys gets increasingly difficult, as managing and moving between these split components need different hotkeys for all three of these approaches.

I made the rule for myself that I don’t use the built-in split functionality of the Windows Terminal, but rather only use two approaches out of the three.

- Open new terminal windows with

Alt+Entereither vertically or horizontally, and let GlazeWM tile them. These windows can be switched between and moved withShift+Alt+i/j/k/landAlt+i/j/k/l, respectively. - Split vim into multiple tabs, and move between them with

Ctrl+i/j/k/l.

I found this approach providing a good balance of being flexible enough, and not requiring too many hotkeys kept in muscle memory.

Community

GlazeWM also has an active and welcoming developer community on its Discord. All the folks I interacted with have been super nice, I got quick answers to all my questions, and useful feedback about some changes I suggested. I highly recommend anyone planning to use GlazeWM as their daily driver environment to join the Discord server.

Summary

I hope this overview was interesting and useful for anyone who’d like to use a tiling window manager on Windows. I cannot reliably quantify how my productivity is affected by using GlazeWM (and whatever time I’m saving I might spend on tinkering with the various configuration options or hacking on the custom Zebar UI 🙂), but it certainly made me excited again about using Windows as an OS for development, and interacting with it a more joyful experience, and I strongly believe that it is already worth it.