Posts in this series:

- Part 1: Hash tables

- Part 2: .NET implementation

- Part 3: Built-in GetHashCode

- Part 4: Custom GetHashCode

Introduction

Recently I came across a situation in which I should have known the details about how a .NET Dictionary (and hashmaps in general) worked under the hood. I realized that my knowledge about this topic was a bit rusty, so I decided I’d refresh my memories and look into this topic. In the first part of these posts we’ll take a quick look into how a hash map works in general, and how those concepts are implemented in the .NET framework.

Hash tables

A hash table (or hash map) is a data structure implementing one of the most fundamental containers: the associative array (1). The associative array is a structure, which maps keys to values. The basic operation of such a container is the lookup, which - as the name suggests - looks up a value based on its key. The hash map is implemented in a way to make this lookup operation as quick as possible, ideally needing only a constant amount of time.

Mechanisms

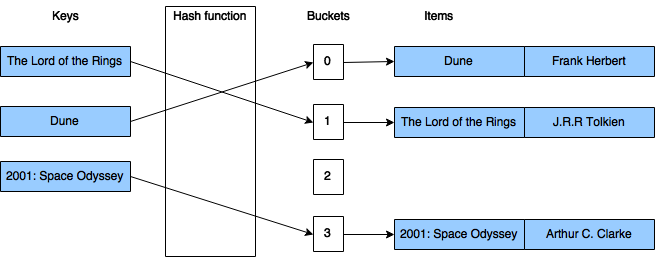

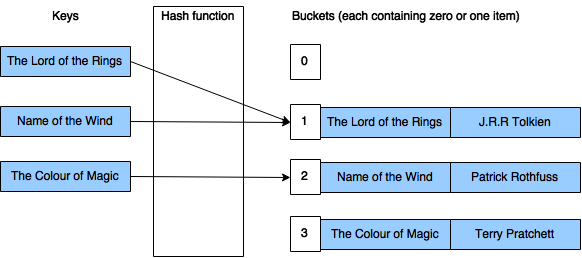

I’ll quickly introduce the most important mechanisms of the kind of hash map which is implemented in .NET. The hash table contains a list of buckets, and in those buckets it stores one or more values. A hash function is used to compute an index based on the key. When we insert an item into our container, it will be added to the bucket designated by the calculated index. Likewise, when we are doing a lookup by the key, we can also calculate this index, and we will know the bucket in which we have to look for our item. Ideally, the hash function will assign each key to a unique bucket, so that all buckets contain only a single element. This would mean that our lookup operation is really constant in its run-time, since it has to calculate the hash, and then it has to get the first (and only) item from the appropriate bucket.

The following image illustrates such a container, which stores some books, where the key is the title of the book (assuming that all the books we’d like to store in this case have unique titles).

But it is possible that the hash function generates an identical hash for two different keys, so most hash table designs assume that collisions can and will happen. When a collision happen, we will store more than a single element in a bucket, which will affect the time needed to do a lookup. In order to make the lookup fast, have to keep the ratio of the number of items and the number of buckets in our container low. This number is an essential property of a hash map, and is usually called the load factor.

Handling collisions

One of the most important concepts in the implementation of a hash map is the way how we handle when two different keys end up having the same hash value, thus their index will point to the same bucket. There are many different approaches, but arguably two of them are the most prominent.

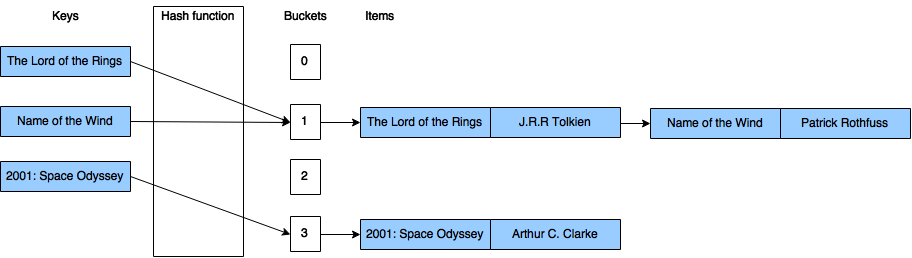

Separate chaining

When using separate chaining, each bucket is handled independently, they all store a list of some kind with all the items having that same key. In this structure, the time needed to find an item is the time needed to calculate the index based on the key, plus the time needed to find the item in the list. Because of this, ideally most of the lists should contain zero or one item, and some of them two or maybe three, but not many more. This way, the time needed for a lookup can be kept low. However, in order to achieve this, the load factor cannot be too high, so we have to adjust the number of buckets to the number of items being stored. The following image illustrates a hash map using separate chaining to handle a collision.

In order to do separate chaining, every bucket should contain a list of items. This can be implemented in various ways, probably the simplest is to store a linked list in every bucket.

Open addressing

In open addressing, the bucket list is simply an array of items, and all the items are stored in this array. This means that if we want to insert an item, but the bucket of the item’s key is already filled, we have to store the item in another bucket. In order to find this “another” bucket to use, a so called probe sequence is used, which defines how we find the alternative position for our item. The simplest of such probe sequences is the linear probing, in which we simply start looking at the buckets following the originally designated position, until we find a free slot.

When we are doing a lookup, if the item in the designated bucket has a different key than what we were looking for, we have to continue looking in the buckets according to the probe sequence until we either find our item, or find an empty bucket (which means that the item is not in the hash map).

Additional details

The above summary was very brief and left out many important details. If you are interested in more information about this topic, a good starting point is the Hash table Wikipedia article (on which most parts of this introduction are based).

Next up

In the next post I’ll look at how these concepts are implemented in the Dictionary class of the .NET framework.