Posts in this series:

- Part 1: Hash tables

- Part 2: .NET implementation

- Part 3: Built-in GetHashCode

- Part 4: Custom GetHashCode

Introduction

In the previous two posts we looked at the basic concepts behind the hash map data structure, and checked out how it is implemented in the Dictionary class of the .NET Framework.

Today we’ll take a look at a very important mechanism behind the Dictionary class: the GetHashCode method, and the way its built-in implementation works.

GetHashCode

GetHashCode is a built-in method in the .NET Framework defined on the Object class, thereby making every built-in or custom type inherit it. I usually feel there is quite a lot of misunderstanding around the purpose and the proper usage of this method. It serves as a default, simple way to use a hash function to generate a hash value for an object. The sole purpose of this method is to use it in the implementation of a hash map, as Eric Lippert states:

“It is by design useful for only one thing: putting an object in a hash table. Hence the name.”

In the Dictionary class, the GetHashCode method is used to get a hash value for a key in order to determine the bucket in which the entry has to be stored.

Built-in implementation

The method is defined on the Object class of the Base Class Library, and it has a default implementation, so we can ask for the hash value of any object. The built-in implementation of the method is different for reference types and value types. Here is a summary about how they work, based on the documentation.

Reference types

The hash code of a reference type object is calculated based on its reference, and not its value, with the RuntimeHelpers.GetHashCode method. What this means is that the value of the hash code does not depend on the values of the object’s fields at all. This can be confusing, imagine that you implement the following class to be used as a key.

public class TestRefKey

{

public readonly int Key;

public TestRefKey(int key)

{

Key = key;

}

}

You store an item in a Dictionary with such a key, then you create the same key and try to get the item from the Dictionary, yet it will not be found.

var dict = new Dictionary<TestRefKey, string>();

var key1 = new TestRefKey(5);

dict.Add(key1, "hello");

var key2 = new TestRefKey(5);

var item = dict[key2]; // This throws a KeyNotFoundException.

In the above example, because the two keys are different objects, even if their internal “state” is the same, we won’t find the object we stored, because the hash code of the reference type object is calculated based on the object’s reference, rather than its value.

If you would like to use a custom reference type as a Dictionary key, you should override its Equals and GetHashCode methods, and make the implementation based on the fields you want to make part of the hash key.

For the above class, the following is a correct implementation.

public class GoodTestRefKey

{

public readonly int Key;

public GoodTestRefKey(int key)

{

Key = key;

}

public override int GetHashCode()

{

return this.Key.GetHashCode();

}

public override bool Equals(object obj)

{

if (obj == null || GetType() != obj.GetType())

return false;

var other = (GoodTestRefKey) obj;

return this.Key == other.Key;

}

}

This way our GoodTestRefKey will have value-type semantics in terms of its hash code and equality, and using it as a Dictionary-key will work properly.

(The equality operator)

As a sidenote: the recommendations about whether you should override the == operator as well are a bit unclear. You can either

- Don’t override the

==operator, so it will still make a reference comparison, but that way you have to be careful about when to useEqualsand==. - Override

==as well, so both comparisons will execute our custom implementation.

The official guide states

“Most reference types should not overload the equality operator, even if they override Equals. However, if you are implementing a reference type that is intended to have value semantics, such as a complex number type, you should override the equality operator.”

I find this advice a bit strange, since if I wanted a type to have value semantics, I would implement it as a struct. A type like the above GoodTestRefKey would also be more idiomatic as a struct in my opinion, I only implemented it as a class now for the sake of the example. (Then again, it only contains an integer, so in this specific case a simple int could’ve been used as the Dictionary key as well.)

Built-in reference types

We’ve seen that the default implementation of the GetHashCode and Equality methods are based on the object’s reference for a reference type. However, this is not necessarily true for built-in .NET types, they might have custom implementation. A typical example is System.String, of which the Equals and GetHashCode is based on the actual characters of the string and they don’t depend on the reference, so using strings as Dictionary keys is safe to do.

Value types:

If the GetHashCode is not overridden for a value type, then the ValueType.GetHashCode method will be called, which looks up all the fields with reflection, and calculates a hash code based on their values. This implicates that value type objects with the same field values will have the same hash code by default, so they are safe to be used as Dictionary keys.

It’s important to keep in mind that the default implementation takes into account all fields in the struct, so a difference in any of the fields will mean a difference in the hash code as well. If we want to have only a subset of the fields affecting the hash code, we should implement a custom GetHashCode method, which I will look at in the next post.

Gotcha: mutable reference type as a key

In the sample code I implemented the GoodTestRefKey to be immutable. This is very important when we intend to use a reference type as a key, otherwise the following scenario can happen:

- We create the key object and set its state.

- Add an entry to the Dictionary with the key. The Dictionary will get the hash code of the object and store the entry in the appropriate bucket.

- We change the state of the key object. This causes the key’s hash code to change as well, but the entry will stay in the same bucket inside the Dictionary, so from now on it will probably be in an incorrect bucket.

- Now the entry is in “limbo”, if we try to look it up by the modified key, we won’t find it, because the lookup will look in the wrong bucket. On the other hand, if we try to look it up with a key with the original state, the entry won’t be found either, since the equality comparison with the modified key will return false.

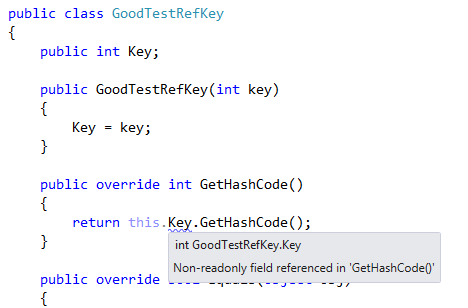

I will illustrate the situation with the little WPF client created for the last post. I removed the readonly keyword from the key’s field to make it mutable.

It’s a very nice touch that Visual Studio displays a warning if we do this:

(After writing this I realized it isn’t VS, but rather ReSharper, so the kudos goes to JetBrains instead of Microsoft in this case :).)

(After writing this I realized it isn’t VS, but rather ReSharper, so the kudos goes to JetBrains instead of Microsoft in this case :).)

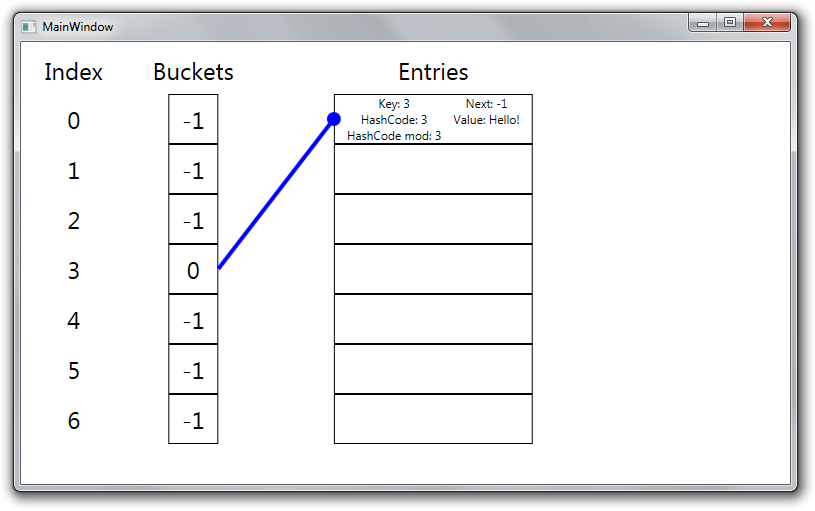

I added an entry to a Dictionary with such a key:

var key = new GoodTestRefKey(3);

var dictWithMutableKey = new Dictionary<GoodTestRefKey, string>(5) { { key, "Hello!" } };

If we display the state of the Dictionary, we see that everything is good, the hash code of the key is 3, and the entry is in the proper bucket:

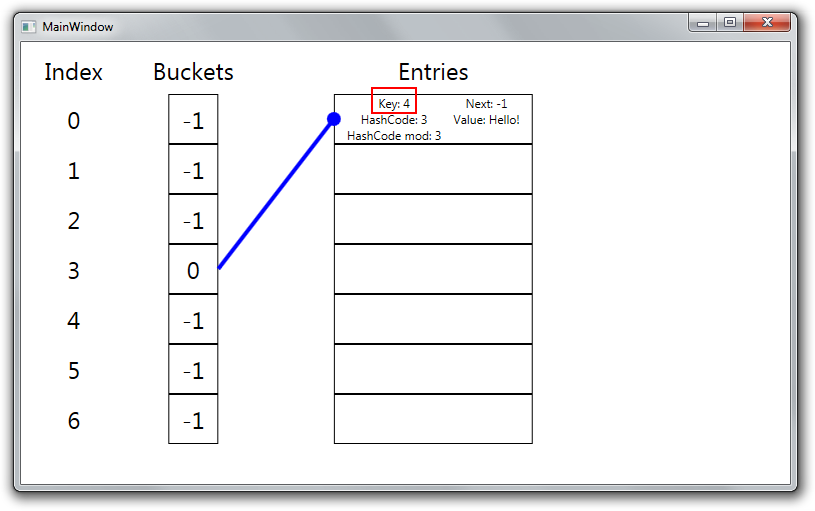

If we mutate the state of the key object

key.Key = 4;

And visualize the Dictionary again

You see that the Key’s value was changed to 4, it’s hash code is 4, however, it’s still in the bucket at the index 3. (Note that the Dictionary separately stores the hash code, which still has the original value.)

var key = new GoodTestRefKey(3);

var dictWithMutableKey = new Dictionary<GoodTestRefKey, string>(5) { { key, "Hello!" } };

key.Key = 4;

var obj1 = dictWithMutableKey[key]; // KeyNotFoundException

var obj3 = dictWithMutableKey[new GoodTestRefKey(3)]; // KeyNotFoundException

var obj2 = dictWithMutableKey[new GoodTestRefKey(4)]; // KeyNotFoundException

If we mutate the key object, we won’t be able to retrieve our entry with any of the above approaches.

- In the first case we will look for the item in a different bucket.

- In the second approach we will look at the right bucket, but the equality-comparison of the keys will fail, since they are different.

- Same as the first case.

But even if one of these approaches managed to retrieve our entry, this situation should be generally avoided.

The rule of thumb to follow in order to avoid this is to only use immutable objects as keys. (Or at least the fields which take part in the hash code generation and the equality comparison should be immutable.)

In the next post I’ll take a look at what to consider when implementing a custom GetHashCode method either for a reference or a value type.