Posts in this series:

- Part 1: Hash tables

- Part 2: .NET implementation

- Part 3: Built-in GetHashCode

- Part 4: Custom GetHashCode

Introduction

Last time we saw an overview about the basic concepts behind a hash map.

In this post we will take a look at the .NET Dictionary class, and see what type of hash map it is and how the different mechanisms have been implemented in C#.

In order to investigate, I used the Reference source published by Microsoft, which contains the code base of the .NET Framework, in which we can look under the hood of the System.Collections.Generic.Dictionary class.

Data model

Every object stored in the dictionary is represented by an instance of the Entry struct:

private struct Entry

{

public int hashCode;

public int next;

public TKey key;

public TValue value;

}

The roles of the hashCode, key and value fields store the core pieces of data every entry has, the key and the value of the entry, and the hash code calculated for the key. The field next plays a role in the implementation of collision resolution (see later).

Every entry lives in an array of Entry objects, which is a field of the Dictionary class:

private Entry[] entries;

This can be a bit confusing, but this array is not the list of buckets we looked at previously. The key and the hash of the key have no relation with the index at which an entry is stored in the entries array, it is rather incidental.

The buckets of the hash map are stored in a separate array:

private int[] buckets;

This is a simple array of integers, where every value in this array points to an index in the entries array, at which index the first entry of that bucket is stored. I write first, because a bucket can contain more than one elements in case of a hash collision, since the .NET Dictionary uses a variant of the technique called chaining to resolve collisions, which we looked at in the previous post.

Some observations

- When using the hash of a key, we want to map the hash to an index in the

bucketsarray, which we do by calculating the remainder of the key divided by the number of buckets. Because we need an index, we want to avoid having negative values, so in many places the code calculates the logical bitwise AND of the hash and the value0x7FFFFFFF, thereby eliminating all negative values. - When a collision happens and two entries fall into the same bucket, they will be chained together using the

nextfield of the Entry. It will point to the next entry, and it has the value -1 if the entry is the last in the chain. - Until we don’t remove any elements, the

entriesarray will be consecutively filled with elements from the 0 index, any new items will be added atcountposition.

When we remove an element, we create a “hole” in this array. This hole will be pointed to by the fieldfreeList, and the number of free holes will be represented byfreeCount. These free entries will be chained together with theEntry.nextfield, similarly to how collided entries are chained together.

Inserting items

The following code fragment shows how the Dictionary handles insertions (simplified, comments by me):

private void Insert(TKey key, TValue value, bool add)

{

// Calculate the hash code of the key, eliminate negative values.

int hashCode = comparer.GetHashCode(key) & 0x7FFFFFFF;

// Calculate the remainder of the hashCode divided by the number of buckets.

// This is the usual way of narrowing the value set of the hash code to the set of possible bucket indices.

int targetBucket = hashCode % buckets.Length;

// Look at all the entries in the target bucket. The next field of the entry points to the next entry in the chain, in case of collision.

// If there are no more items in the chain, its value is -1.

// If we find the key in the dictionary, we update the associated value and return.

for (int i = buckets[targetBucket]; i >= 0; i = entries[i].next) {

if (entries[i].hashCode == hashCode && comparer.Equals(entries[i].key, key)) {

entries[i].value = value;

version++;

return;

}

}

int index;

if (freeCount > 0) {

// There is a "hole" in the entries array, because something has been removed.

// The first empty place is pointed to by freeList, we insert our entry there.

index = freeList;

freeList = entries[index].next;

freeCount--;

}

else {

// There are no "holes" in the entries array.

if (count == entries.Length)

{

// The dictionary is full, we need to increase its size by calling Resize.

// (After Resize, it's guaranteed that there are no holes in the array.)

Resize();

targetBucket = hashCode % buckets.Length;

}

// We can simply take the next consecutive place in the entries array.

index = count;

count++;

}

// Setting the fields of the entry

entries[index].hashCode = hashCode;

entries[index].next = buckets[targetBucket]; // If the bucket already contained an item, it will be the next in the collision resolution chain.

entries[index].key = key;

entries[index].value = value;

buckets[targetBucket] = index; // The bucket will point to this entry from now on.

}

Illustration

I created a small class library and GUI app for two purposes:

- Dive into and extract the internal state of a Dictionary instance using Reflection

- Visualize the hash map in a neat diagram

(You can find the source code for the lib and the tool in my GitHub repo, sorry for the ugly WPF code, “MVVM, you must be kidding” :))

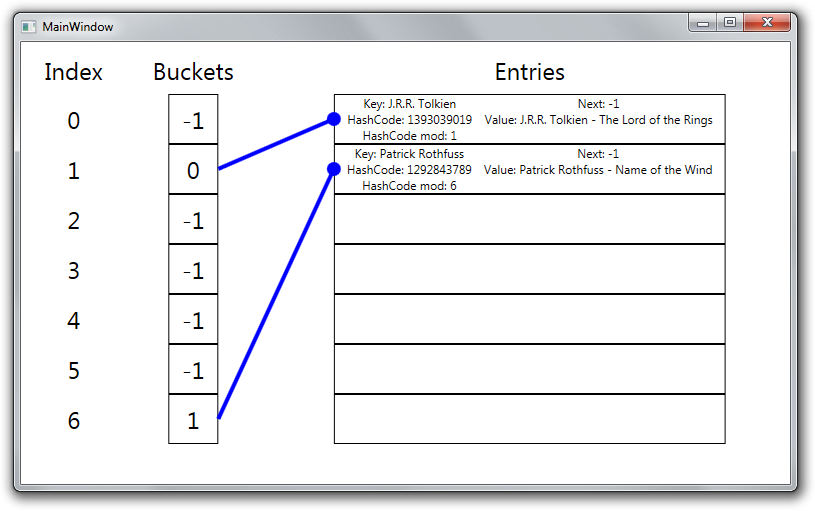

The tool displays the buckets array, which contains indices which point to records in the entries array, and shows the details of the actual entries.

I created a helper class which represents a book with an author and a title. We will use the author as a key to store the books in the dictionary. First I’ll add two books to the dictionary. Luckily the hashes of the keys from these two books will not collide:

var book1 = new Book("J.R.R. Tolkien", "The Lord of the Rings");

var book2 = new Book("Patrick Rothfuss", "Name of the Wind");

var dict = new Dictionary<string, Book>(5)

{

{ book1.Author, book1 },

{ book2.Author, book2 },

};

With these two items, the internal structure of the Dictionary looks like this.

You can see that the entries are in the buckets designated by their hashcodes, while the Entries array is filled up consecutively.

You can see that the entries are in the buckets designated by their hashcodes, while the Entries array is filled up consecutively.

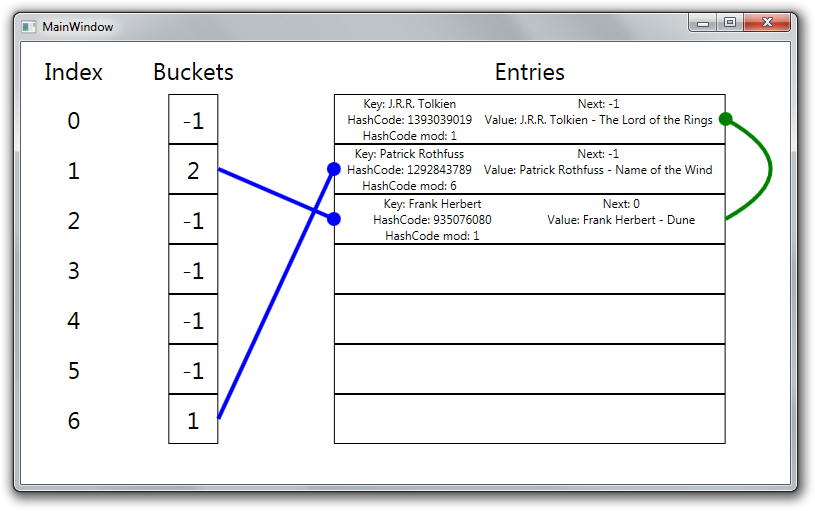

Now we insert a third element of which the remainder of its key hash will collide with an existing entry in the dictionary.

var book3 = new Book("Frank Herbert", "Dune");

We can see that the elements falling in the same bucket are chained together, with the Next field of the entry pointing to the next entry in the chain.

We can say that the .NET Dictionary implementation conceptually uses chaining as its collision resolution method, but it doesn’t use a separate data structure (like a linked list) to store the items in the chain, it rather stores every entry in the same array.

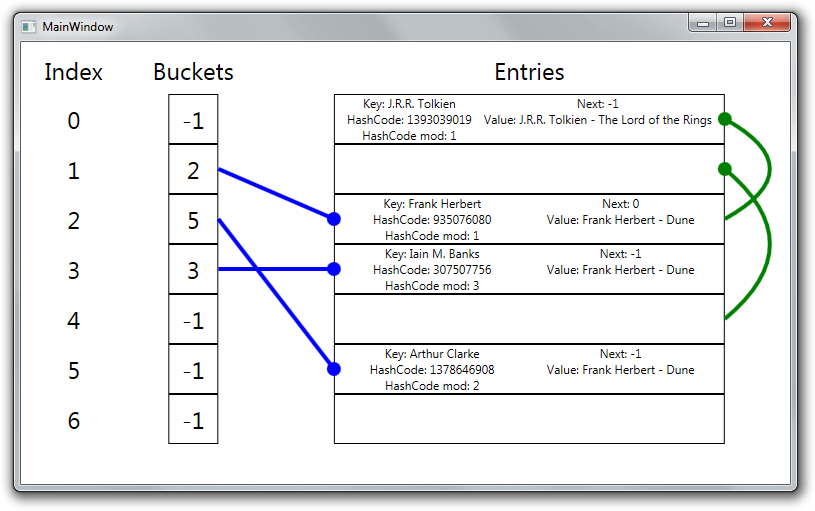

Now we add some more elements to the dictionary, then remove two of them.

var book1 = new Book("J.R.R. Tolkien", "The Lord of the Rings");

var book2 = new Book("Patrick Rothfuss", "Name of the Wind");

var book3 = new Book("Frank Herbert", "Dune");

var book4 = new Book("Iain M. Banks", "Consider Phlebas");

var book5 = new Book("Isaac Asimov", "Foundation");

var book6 = new Book("Arthur Clarke", "2001: Space Odyssey");

var dict = new Dictionary<string, Book>(5)

{

{ book1.Author, book1},

{ book2.Author, book2},

{ book3.Author, book3},

{ book4.Author, book3},

{ book5.Author, book3},

{ book6.Author, book3},

};

dict.Remove(book2.Author);

dict.Remove(book5.Author);

After this, we can see, that the “holes” in the dictionary will be chained together the same way as collided entries are chained.

And in the code fragment above we saw that when we insert items, we always try to fill these holes first, and then use up the free slots at the end of the array.

Summary

With this we got an overview about how a dictionary works. There are other important aspects, like the lookup itself, or resizing the dictionary in case there is no more free space in the array, but I’ll leave it up to you to discover. With the above introduction, the code should be rather straightforward to read.

In the next part I’ll look at how the hash code of the keys are calculated, and what are the pitfalls we have to watch out for when choosing a type to use as a key.